Over the last few years, tactics have become increasingly important in modern football. So much so, that clubs and academies dedicate great human, material and time resources to assistants, analysts, training, technology, software and video analysis systems. This is all with the aim of developing this aspect of the game as much as possible in order to consequently increase the performance of their players and teams.

Although it is true that tactical intentions are a factor that determines performance, Ruíz (2006) tells us that these intentions appear after perceiving the game situation, perception being the key element for the development of the play.

What is the perception and vision of the game?

Perception is the information that the player is able to extract from their environment, distinguishing those inputs from the external environment that are not relevant to the task they are performing at that moment.

We place perception within the information processing model of Welford and Schmidt (1999), which is based on four mechanisms: perception, decision, execution and intrinsic feedback. Thus, the player perceives information from their environment (external inputs), decides on an appropriate response to that situation, executes it and in each of these three mechanisms intrinsic feedback can modify the response, forming a feedback loop.

“The perception and decision mechanisms, even when the player is not in contact with the ball (more than 90% of the playing time) are intensely required. So decisive is their maximum efficiency that a player who perceives and decides correctly and quickly, can diminish the negative impact of a low level of execution” (Sans, A. & Frattarola, C., 2004: 25).

According to Fradua (1997:13) “The playing vision of a football player is the ability to correctly identify the space, the movements of teammates and opponents and to choose the best option among several possibilities” (Sans, A. & Frattarola, C., 2004: 25).

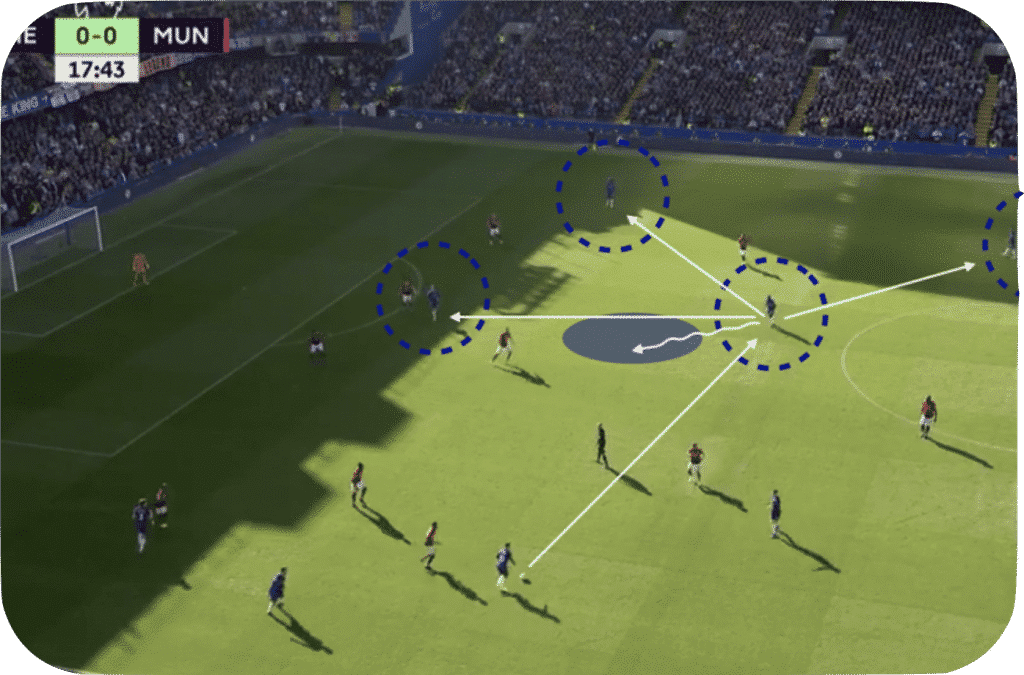

In the situation below, we see that both the player with the ball and the possible receiver have different playing options. In order to select the best one, they must make an accurate perception of the environment and the situation to identify the criteria that will make them make the best possible decision or at least not the worst one.

Why is it important to train perception?

These visual abilities will greatly facilitate the learning and development of content related to perceptual skills, such as the basic fundamentals of the game, as every decision taken in the game will be preceded by a collection of information. Consequently, they will be able to find the solutions to the different problems that the game poses more easily.

In short, actively and correctly gathering information about the events of each situation will help them to make the best decision among the different options offered by the game. Hence, expert players are able to generate more solution possibilities than young players, using visual resources in a much more effective way.

This idea is reinforced by the author Jorge Castelo, who explains that when players are stimulated to develop the principles of the game, they accelerate their decision making in the resolution of the different and complex problems of the game. But also, they establish informative codes that provoke a better perception on the part of team mates by identifying more quickly what tactical intentions they have.

How to train perception?

At the MBP School of Coaches, we believe that in order to maintain the specificity of the competitive context (ecological context), the player must live in constant uncertainty, perceiving and acting through the information the player obtains. The process of decision making and subsequent action is interdependent, forming a constant cycle of responses between perception and action (Gibson, J. 1975).

In MBP we categorise the content of perception into five different blocks: centre of play, near spaces, far spaces, body orientation and scanning. At a higher level of specificity, we use what we call the information search criteria (ISC).

This is nothing more than the aspects to be observed according to the strategic role played by the player in the game situation; attacker with the ball, attacker without the ball, defender, or in other words, the concepts. In addition to this distinction, for the training of perception, we will need to set open tasks, in which the player does not initially know what exactly they must do to solve the problem that is presented. In this way, we will ensure that they have to be as cognitively engaged as possible, just as they will have to be during competition.

This type of task follows the principles of ecological theory and the concept of enactivism of Jaegher & Di Paolo (2007). These two authors say that enactivism has a fundamental role in the action or movement during the player’s perception, where it attributes much importance to self-organisation and emergence – concepts seen in football studies – in order to perceive in dynamic systems.

With the intention of gradually bringing the player closer to the different game situations that we propose, we will design training tasks that consider the level of specificity that these play (Camenforte et al., 2021), always respecting the principles of globality, openness, enactivism and specificity.

Below is an example of a Discontinuous Invasion Game focused on training the block of the perception of far spaces.

References

Camenforte, Ismael & Casamichana, David & Cos, Francesc & Castellano, Julen & Fernández, Javier. (2021). Diseño y validación de una herramienta de valoración del nivel de especificidad de las situaciones simuladoras preferenciales en fútbol. [Design and validation of a Specificity level assessment tool for preferential simulation situation in football].. RICYDE. Revista internacional de ciencias del deporte. 17. 69-87. 10.5232/ricyde2021.06306.

Gibson, J.J. (1975). Events are Perceivable But Time Is Not. In: Fraser, J.T., Lawrence, N. (eds) The Study of Time II. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-50121-0_22

Ruiz de Alarcón Quintero, Anselmo (2006) Análisi de la iniciación al fútbol. EFDeportes, any 10, no92

De Jaegher, H., & Di Paolo, E. (2007). Participatory sense-making: An enactive approach to social cognition. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 6(4), 485–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-007-9076-9

Sans, A. i Frattarola, C. (2004). Entrenamiento en el fútbol base -AT1-(2a ed.). Barcelona: Paidotribo

Schmidt, R.A.; Wrisberg, C.A. (1999). Motor learning and performance. Champaing: Human Kinetics.

Fradua, L. (1997). La Visión de juego en el futbolista. Barcelona. Paidotribo.